The A Cappella Cookbook

I am Bob Eggers - singer, director, arranger. I sang with and directed Yale's Society of Orpheus and Bacchus. I also sang with and directed the Yale Whiffenpoofs of 1973. I also helped the Whiffs restore their legendary Songbook - nearly 100 songs now and going strong. I am in the field every day making music, composing, arranging, playing, singing, recording, restoring old recordings, publishing music, manufacturing and selling music both on the Web and in brick and mortar operations.

Saturday, July 6, 2013

The Yale SOB's Birthday

Saturday, June 15, 2013

A New, Old Whiffenpoof

Sunday, January 29, 2012

Why Are We Doing This?

One of the more challenging things a musical director does is teaching non-professional singers to be expressive. We teach so many mechanical skills - the notes, the rhythms, the entrances and the lifts, how to form vowels with the lips, tongue and throat; the list goes on and on. If your choir is working on all of these things they will sound good, but maybe not great.

If your singers can also express emotion, something truly amazing can happen. Have you ever noticed how sometimes "magic" happens seemingly on its own, and you touch something beyond yourselves? Maybe the mood of the singers is right, the acoustics are particularly good, and the nuances become evident to the average singer so each can lend more attention to the emotional content of the material. We all love these moments. This is where you want to be every time you sing.

Get To the Point

A great choir is a bunch of regular people who master the little details regardless of the conditions and endeavor to "get to the point" every time they sing. They don't have to all be great divas. Your singers must realize their primary job is just this. They need to reach into the heart and soul of a piece and craft a sound that will project that core emotion into the heart of the listener. As a singer, you can't do it reliably by merely going with the flow or hiding in the ranks. You need to be the flow.

Yes, it is craft. Your singers should not be emoting, drawing pictures for the audience. Instead, they want to be mindful of the emotional center of the piece and employing the appropriate mechanics to express it. This cannot be done without conscious effort and practice. When you sing a sad piece 100 times, it will not make you feel sad anymore. Chances are good you'll be half asleep and forget to apply the technique needed to express the core emotion. And if you have let practice go by without working on this aspect - it's not generally going to happen spontaneously once you're in front of 100 people.

We have one song that's about fierce jealousy. At one rehearsal we spent some moments recalling expressions of this emotion we'd witnessed or experienced, and considered how it affected speech. The jealous or angry person puts a sharp edge on all consonants - he or she works the words much harder, actually turning them into weapons. If this aspect is missing from a song about jealousy, it simply won't do the job.

As an a cappella singer, you have nothing to inspire you but what you find within. There are no sad violins or grinding electric guitars to grease the skids for you. It all comes from inside. You are it.

A Case Study

I told this story before, but it's a good one: After one of our programs, a woman came up to me and complained about a song we'd sung, Monk's "Round Midnight". She really liked our show, but said we should never had sung that song, adding it was terrible that we'd done it. I thought we'd done a good job with it and had to ask her why she felt this way. She told me very clearly that it reminded her of her longing for her lost husband and had made her cry. Now I understood - our little arrow had hit the mark and opened her heart. This is so important, and by this I don't mean our mission is to bum people out. I mean to put them back in touch with themselves, so they can be human to others, so they can empathize with others and be better human beings in every part of their lives. With art and song, we have the power to do exactly this. It's huge!

Hit the Spot!

This is such an important aspect of what your choir is doing - in fact there's really no other good excuse for standing in front of an audience if you are not aiming for this. "Magic" will not happen for the audience just because you're covering a particular song. In fact, if your message does not "hit the spot", your audience will not experience "flow" - they will not forget themselves and arrive at a place where time no longer exists. This is the place where the whole world can be healed.

This is what you are doing.

Thursday, September 15, 2011

Copyrighting Your Work

In the past few months I copyrighted quite a number of my arrangements, 55 to be exact! Today, you can do this on the Internet by visiting http://www.copyright.gov/, and creating an account for yourself. Before you begin, prepare all of your music so you'll be ready to submit it at the end of the application process. I'll describe this further below.

You can copyright only the arrangement, declaring very clearly you take no credit for the melody or the lyrics. Through the process, the application forms make this all very clear. Be sure you are taking credit for original work on your end, not a recasting of someone else's work. If you adapt another person's work and change 20%, 30% or even 80% of it, it's really not original.

You'll need nothing more than PDF files of the sheet music. Be sure to include a copyright notice on the first page of every song before making your PDF files. Basically you sign up with copyright.gov and tell them what you want to copyright. If you have a number of songs, you can copyright a "book" for one low fee. You list all the songs in the book, and once the whole set is defined, make a payment using a credit card for the $35 handling fee, and upload each song at the end. Leave yourself plenty of time for this task, and don't worry too much about the sometimes cryptic questions. Humans receive and process all your information on the other end, and they're really quite good at figuring it all out.

Then what?

You wait. When you think you've waited enough, wait some more. There's a lot that has to go on on the Government side, and there is also a long queue of requests. So be patient and do not doubt. If something is screwy with your application, they will contact you and straighten it out. This is not like buying stuff at Amazon.com. In a few weeks or more, you'll receive confirmation by regular mail with your official copyright numbers for your stuff. It's not exactly suitable for framing, but it's pretty cool.

So what next?

More arranging and getting more of my stuff "out there". I am actively marketing my stuff to various choirs. This year, I expect to hear one of my new arrangements sung by the Society of Orpheus and Bacchus, and I am very excited about that! I sent it off speculatively to the new music director, Paul Leo, last spring, and he liked it a lot. We had a little discussion about arranging. He was looking ahead to his new role and wondering how he would rise to the occasion. As Orpheus, he is expected to introduce new, original material and keep the group moving forward creatively. Every director wants to contribute one or more new pieces of work, and they want them to become favorites for years to come.

Tools and Tricks

As I told Paul, I heard Deke Sharon is developing a book on a cappella arranging. I see there's another well reviewed book, "The Collegiate A Cappella Arranging Manual" by Anna Callahan. The Barbershop Harmony Society also publishes an incredible 450 page "Barbershop Arranging Manual" on the topic. References like these need to be within reach while you work.

But one of my main tools, as I told the new SOB director, is my MP3 player. First I hunt around for songs of interest to me. I suggest casting a wide net in the early stage. I buy a slew of versions of any interesting songs, and I load up my MP3 player with them. You can use your smart phone as I do (Palm Pre) or iPod or iPod Touch. It's great to have something pretty rugged, because the next step is to set aside a time to listen and for me that means while working out at the gym.

The goal is to play the list over and over, day in and day out, for 30-60 minutes a day while your mind has nothing else to do but let it sink in. When I was a student of Thich Nhat Hanh, I learned something called "deep listening", and this practice comes in handy here. You let the songs inhabit your mindspace, bounce around inside your subconscious, and eventually your ideas about how you "hear" each song begin to coalesce. Eventually, you can conceive your treatment of one of these songs from start to finish. This is not the same as knowing every note and rest; it is most likely a very broad brush conception with some parts in greater focus than others. But at some moment on the treadmill it will hit you as a complete concept after which you will find the momentum to direct 100% of your attention to realizing the concept with black dots, stems, rests and all sorts of other bits of ink on paper.

Monday, August 15, 2011

In Search Of...

Restoring the musical archives of the Society of Orpheus and Bacchus has led me on a journey into the past, back to the earliest moments of the organization. Very little is known today by most alumni or current members. The mists of time have been cast over the events of nearly 75 years ago, as the story has been told and retold like a parlor game of Chinese Whispers.

We recently conducted an interview with our founder, Irving Walradt, class of 1941. Irving still has all his wits about him. The words he used were simple enough, but we did not grasp what he was saying. It was so different from the myth we'd created, so different from the projections of our reality that we could not hear his message.

History Made Every Day

After more research, more discussion, unearthing some photographs and a few more stories, the mist has begun to clear and now we're beginning to get it. Not all of us, mind you: We've told another story to ourselves for so long we may not be able to supplant the myth with the reality.

We have member rosters going back to the class of 1940, and we considered those men sang with the group in the year or so previous to graduating. In my day, we had an oral history that pinned the group's founding to 1939. Today, the group's oral history has backed that up to 1938. But Irving told us a story that made it look more like 1940, although he said there was an informal group singing with our name the previous year. But, he said they would never have endured without him founding the group to, in his words, "last forever".

Where Did We Begin?

So, what to make of this? Perhaps the group had been around as an informal organization when along comes our "founder" to establish some order that carries us to the present day. Isn't this just a man saying he added essential structure while clearly another kind of founding, of equal importance, had preceded his contribution? Didn't Irving just join those guys and augment what was already there? When was the moment of inception? Was there such a moment, or did we begin in a more organic and evolutionary way?

That's where we were after reading the extensive interview with Irving. After all, he told us the men we listed as our first members were singing together the previous year, but asserted it was he who had really founded the group. Reading his interview, we assumed that the group already existed in 1939, a story consistent with our shared myth, and along he comes, the first true Orpheus/Pitchpipe and sets a structure in place.

It Didn't Happen Like You Said

But it turns out that's not what happened at all. Over the last few months I've been digging into the deep past, reading histories, pumping the alumni for stories and photos and generally shaking trees to see what fruit falls out of them. As part of that process, I wrote to Irving at his home to request any old photos he might have of himself or the group. For weeks I'd heard nothing.

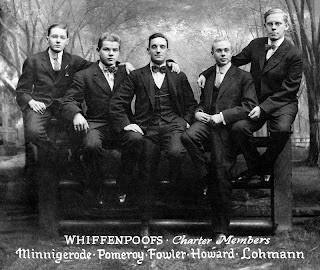

A couple of weeks ago, I took a day off to visit New Haven and archive some Whiffenpoof music in the Whiff Alumni office in Mory's and met Barry McMurtrey, SOB alum of the class of 1988, for lunch. Barry works at Yale's Sterling Library. As we waited for our meal, Barry showed me the "oldest known photograph of the SOBs". It was extraordinary, of extremely high quality, with 4 guys looking very dapper, and quite hip, singing a song in the open sun next to a 50 pound bag of oranges hanging on a hook. Barry told me he'd been given the photograph by Bill Oler, founder of the modern Spizzwinks and class of 1945, whose elder brother Wesley appeared at far left in the photo. Bill Oler had told Barry it was the oldest known photograph of the Society of Orpheus and Bacchus and had been taken on the historic Glee Club trip to South America.

The photograph had a sort of cover page wrapped around it, printed with the words Yale Glee Club Spring Trip of 1940, and noted the names of the men in the photo, calling them the Orpheus and Bacchus Association, also abbreviated, "OBA". We both knew of the historic trip to South America, and here was a shot in some tropical climate with what must have been the original name of our group: the OBA rather than the SOBs.

Who Are These People?

In it we saw what we wanted to see: four of our guys, maybe the very first guys Irving had described, singing informally together before he came along, before the group's name was "improved". Barry promised to scan the photo and send it to me. But after I returned to Boston, he wrote me that the names of two of the men were not in our official roster and so he no longer knew what the picture represented. We were suddenly very confused. I mean, hadn't Irving joined these guys the following year and formalized the organization? Barry was asking the right question: How come we didn't know who these guys were?

The OBA Quartet

I convinced Barry to send me the photo so I could send it to Irving and ask him to explain things to us. Once I got it, I checked in Tim DeWerff's "Louder Yet the Chorus Raise", a history of the Yale Glee Club to see whether these names were in the rosters Tim included in the appendices. Sure enough, all four men appeared in the roster for 1940. I thought, "it's merely an oversight - just add the names to our roster and move on".

The next morning I was at the gym and ran into a friend of mine from Polymnia and we started talking. Somehow the conversation turned to his father and he mentioned he was reading his father's journal from his trip with the Yale Glee Club to South America in 1941. Wow, I said, I was just looking at a photo from that trip and probably your dad knew these guys! But something stirred in my brain - the photo was marked as 1940 and my friend had said 1941. When I got home I check in DeWerff's book once more and saw the SA tour was in the summer of 1941. These were two different trips!

What Year Is It?

Then I looked closely at the Glee Club rosters in DeWerffs appendix, listed neatly year by year: 1939, 1940, 1941... and noticed that any given name only appeared in one list. The veil was slowly lifting from my eyes as I realized the Glee Club was run like college sports in those days. There was a Freshman Glee Club, then the Apollo (Junior Varsity) Glee Club and finally the Varsity Glee Club. Basically you had to rise up in the system to make it into the Varsity Glee Club, typically as a senior. Aha! These guys were all class of 1940, and they were all in that list. Irving was class of 1941 and appeared in the next list. Slowly the fog lifts a bit more...

A few days later I received Irving's reply to my request for photos. It came in a large manila envelope and included a two page, typewritten letter and an 8x10 B&W photograph of 8 men in white tie and tails. In the letter, Irving repeats his founder's story again and describes the 8 men as the first SOBs. Those other guys before "us" might have been SOBs, but that stood for you-know-what. His group was made up of seniors, juniors and sophomores, and had received their name "Sons of Orpheus and Bacchus" from the great Marshall Bartholomew himself.

Dawn Over Marblehead

Now my eyes opened fully and the light came shooting in. For a year or maybe more a bunch of seniors in the Varsity Glee Club had formed a pickup group and had some fun singing on the Glee Club tours. Perhaps they operated under the working name of Orpheus and Bacchus Association, a name inspired by their love of drinking and singing or maybe had been loosely given them by Barty.

But these guys graduate each year and are gone. Maybe a new pickup group repeats the following year or maybe it fades into oblivion. That's how the OBA was working, and that's who is depicted in the photo Barry had gotten from Bill Oler.

But Irving is admitted the Varsity Glee Club in the fall of 1940, and because he was not tapped for the Whiffenpoofs, has decided to start his own a cappella group. He picks guys from the underclassmen in the Apollo Glee Club so they will have longevity, puts together some cool arrangements for them, among them "Pretty Girl" and "Old Gray Bonnet". Marshall Bartholomew is thrilled and dubs the group "Sons of Orpheus and Bacchus". It is an historic moment. Up until this time, the Whiffenpoofs and senior pickup groups like the OBA perform break out numbers or sing to entertain one another on Glee Club tours. Now an a cappella group including undergraduates is included in the fun. Barty often invited the SOBs to tour with the Glee Club for the rest of his tenure. And "Pretty Girl" is still sung to this day to close every SOB concert.

The first SOB's

Irving chooses his voices with care, but also sizes up his lieutenants and establishes a leadership succession. It turns out to be enough to last forever.

The Whiffenpoof Blue Book

One last note before I sign off. As you know, I do archive work for the Whiffenpoofs. Many years before I got involved, the first archivist for the Whiffenpoofs was the aforementioned Bill Oler, 1945. One of the things Bill did, in addition to re-founding the modern Spizzwinks, was gather up all the music the Whiffenpoofs were singing and put it together into a book that came to be known as the Whiffenpoof Blue Book (WBB). In the process, he consulted with his older brother Wesley, from the OBA, and probably got manuscripts from him as well. Wesley and Bill were not able to establish who had arranged many of the songs; sometimes Wesley was able to tell him. There are notes on several of the WBB manuscripts to substantiate what I'm saying. But to this day most are still "Arrangement: WBB" meaning, "we don't know", including such songs as "Pretty Girl" and "Old Gray Bonnet".

In the interview with Irving, we also collected some of the first songs sung by the SOBs, including Irving's arrangements of "Pretty Girl" and "Old Gray Bonnet" and added them to our archives. These two songs are also in the Whiffenpoof archives, part of the WBB. In a court of law, under oath, I'd have to testify Irving Walradt '41, could well deserve the credit for arranging both of them.

Saturday, April 16, 2011

Sunday, March 13, 2011

Arranging 101, Semester 2: A Case Study

Back in 1954 or 1955, one of the great musical directors of the Society of Orpheus and Bacchus, whose first name is Pete, arranged a classic piece the group sang for the next 20 or 30 years. We're not sure whether Pete made a chart of the song - if he did it was lost well before 1958 when another great director, first name of Chan, was singing it. It appears to have been passed on entirely by oral tradition. I sang this song with the O's & B's in the early 70's and I could swear we had charts for it, but nobody has yet located a copy. I went looking for records of this arrangement recently, and luckily we found something.

It turns out one of the O's & B's from the 90's made a project after graduation to pull together the ragged archives and bring some order to the chaos. He noticed the music for this particular song was missing, and contacted Chan to ask him to work up a sketch. This sketch is what was found a few weeks ago, and was sent to me.

So What's the Song?

Oh, yeah - almost forgot.... The song is a medley of two great American classics. First, "Sweet Sue" by Will Harris and Victor Young. The second is "Honeysuckle Rose" by the great Fats Waller with lyrics by Andy Razaf. Pete found a way to combine these, creating a duet by combining the two songs at once, what is generally called a fugue. Fugues are never easy to construct, but they are absolutely delightful to the ear. So our lost piece is remarkable in this respect, making it even more worthy of attention.

Chan's sketch represents to a great extent how his group had learned the song via oral tradition. If you've sung in an informal group like the SOBs, you will know this means they singers have improvised their parts over the years. Often times, the original complicated ideas are lost. There are really two reasons why these things get munged. First, the more complicated ideas are often hard to sing. The singers struggle with these sections, get them wrong, and they end up turned to mud or into something that sounds more familiar to their ears. Second, they may get altered by design, to firm up the core of the original concept in a way the singers can latch onto. They get rearranged, sometimes for the better and sometimes for the worse.

I'm not going to get into how singers wing it through these difficult sections. It's a complicated, non-directed, organic process that rarely produces a remarkable or stable result. But arrangers who introduce their work to singers and identify these sticky wickets need to react quickly to redesign them before they are transmogrified to perpetual mud.

Chan's sketch also represents an extension of the arrangement beyond the way it was sung by his group in 1958 or so, because Chan is always working on solving problems and he's always learning new tricks.

Restoring 101

If you have such a sketch and some old recordings, as I also did, you can begin the work of restoring a piece like Sweet Sue/Honeysuckle Rose, and begin to see all of these dynamics at work. You also a learn a little bit of history on the way. I have a 1954 recording with Pete and his group singing the song. I also have a 1961 recording of Chan and his guys singing a somewhat different rendition. In addition, I have my own experience singing it in 1970.

First, I started with Chan's sketch and punched it up to a full-fledged manuscript. Then I compared it very closely to the recording his group had made, looking for embellishments and changes he'd added due to his basic creative nature. Essentially, this turned the clock back from the 1990's back through 1970 when I sang the song, all the way back to 1958.

Then, I took that version and tried to line it up with the recording of Pete's group singing in 1954. I stripped away embellishments of a few years, reverse engineered a few things and arrived a very good guess at Pete's original construction. Yes, nothing more than a good guess, in spite of having a decent recording.

The Rosetta Stone?

You think it would be, but in truth, the 1954 recording is not the decoding ring we seek. Why? Because Pete was darn clever and the guys just could not sing what he'd put together. In the recording, they fudge the tricky parts, which come out like pure mud. Pete was not able to get these passages under control. Look, in those days the charts were all prepared by hand, and the singers' copies were also recopied by hand. True, Xerox copiers were invented in 1938, but not available for sale until 1958. So arrangers stuck to what they written and were not able to react quickly as one might do today.

So along comes Chan in the summer of 1958, and he transcribes pretty much the entire repertoire, including pieces only in the oral tradition. One reason he's able to do so is the College has copiers! Let's look at two of those tricky spots, and see what Chan was able to do to get the mud out of them in 1958.

Dissecting Clever Rearranging

There's nothing better than concrete examples! I'll be using examples set in the key of F below. Since the key signature is clipped from the images, don't forget the B is flat by default!

First, measure 41 and following, where the ensemble sings, "Don't buy sugar". You'll see first what Pete was trying to do, something I've guessed at from the muddy section of the recording. Reminder, we're in the key of B flat here:

You can see the progression he uses is:

F/C - Em7b5/D - Ddim7 - Adim/C.

This is my best guess, mind you because there is no manuscript, and the singers are winging it all over the map. Now, take a look at Chan's rework of this passage:

Chan takes this section, extracts the key voice leading ideas, alters them slightly to strengthen them and harden up the chords. What do I mean by hardening up the chords? Look at those chord names above and you'll see there are quite a few modifiers and qualifiers to express a couple of the chords. These are Chan's chords in the same passage:

F7/C - Cm7 - Ddim7 - F7

First of all, the simplification of the 2nd chord to Cm7 helps, and Chan gets that Pete's summation chord, the Adim/C is really an F7, so he firms that up. The sequence is cleaner, the voice lines less tricky and more definite. This makes it easier for the singers to audiate their lines, and to follow the less ambiguous chord progression. Take note of something interesting: on the piano, both passages sound almost equally good.

Just a couple of bars later, there's another muddy passage on the 1954 recording, at measure 46 and following, where the ensemble sings, "You're his sugar." This, is my best guess at Pete's 1954 version:

Note, we're still in B flat, and Pete's chord progression there is G - D7 - Edim7 - G7/D.

Now, look at Chan's rework of this passage to bring it into better focus:

Chan's chords are not that different: G - D7 - F#7 - G7. But the third chord is quite different and has less modifiers - it's less ambiguous and works to clarify the harmonic sequence. And the summation chord is a solid G7, with a real rather than an impled G, and without the 5th in the bass. The main thing it allows is for the bass line to trace the roots of more definitive chords as it ascends. This anchors the singers in the unfolding harmonics.

Again, notice that on the piano, both voicings sound almost equally good. Chan has grasped something about these two passage that solves the observed problems singing them.

Spiff it Up

So today you have a computer, rather than pencil and paper, and not only is it easy to make copies for your singers, it's also easy to rework a section that's too clever for words, and can't easily be sung. Take advantage of this technology and make your adjustments early on, before your singers turn things to mud and invent some less than acceptable accommodation that will never sound right.